by Professor Peter Barrett,

Emeritus Professor, University of Salford

Honorary Research Fellow, University of Oxford

Introduction

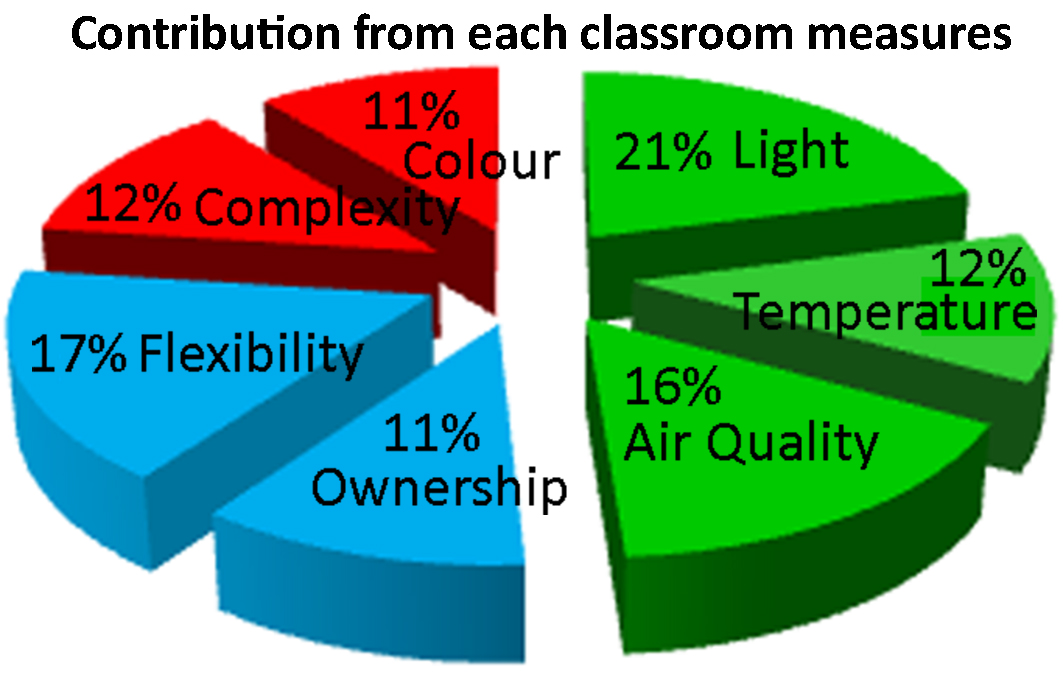

The HEAD (holistic evidence and design) study delivered the evidence that the physical characteristics of the classroom do impact very significantly on the learning progress of primary school pupils. Taking everything together the measured impact of the classroom design factors accounted for 16% of the variation in learning of the 3766 pupils in the 153 classrooms assessed. The academic results and the “Clever Classrooms” illustrated guide for teachers and designers, plus other related material, are all freely available at www.cleverclassroomsdesign.co.uk.

In order to carry out a study that really took the viewpoint of the pupil in the classroom, a novel SIN model was developed to guide the data collection and analysis. The results showed that the “N” (naturalness) factors accounted for just under a half of the 16% impact. This is great to evidence, but is perhaps fairly expected given it includes really quiet basic issues such as sufficient light, good air quality and effective temperature control.

The level of ambient stimulation (“S”) provided by the visual complexity and colour of the classroom environment is an issue that had often been debated, but about which there was little consensus. The HEAD results clearly showed that a mid-level of stimulation is optimal for learning – not too chaotic and not too boring. Obvious maybe, once you know!

Perhaps the most novel element of the HEAD approach was the proposition that the level of individualisation (“I”) is important for learning. This was driven by consideration of how people process sensory information in their brains and the fact that as individuals we build up preferences. This is at a group level, that is, things that are appropriate for say young children, and at the level of the single person, where having options is key in relation to classroom design. To test out these ideas about individualisation, two aspects of the classrooms studied were considered: the “ownership” and the “flexibility” they offer the pupils and their teacher. The HEAD findings on the impact of individualisation are very surprising. Not only are the factors involved statistically significant in their impact on learning, but the scale of the effect is big – between a quarter and a third of the overall 16% impact is accounted for by “ownership” and “flexibility”.

This article will now focus in on the issue of individualisation and the practical opportunities it presents to optimise the primary school classroom for learning.

Ownership

This concerns the creation of a space that the children feel is theirs, because it has character, has their marks as individuals on it and is properly set up for people of their size and age. These are quite simple issues in one way, but involve a wide range of actions to achieve the full effect possible.

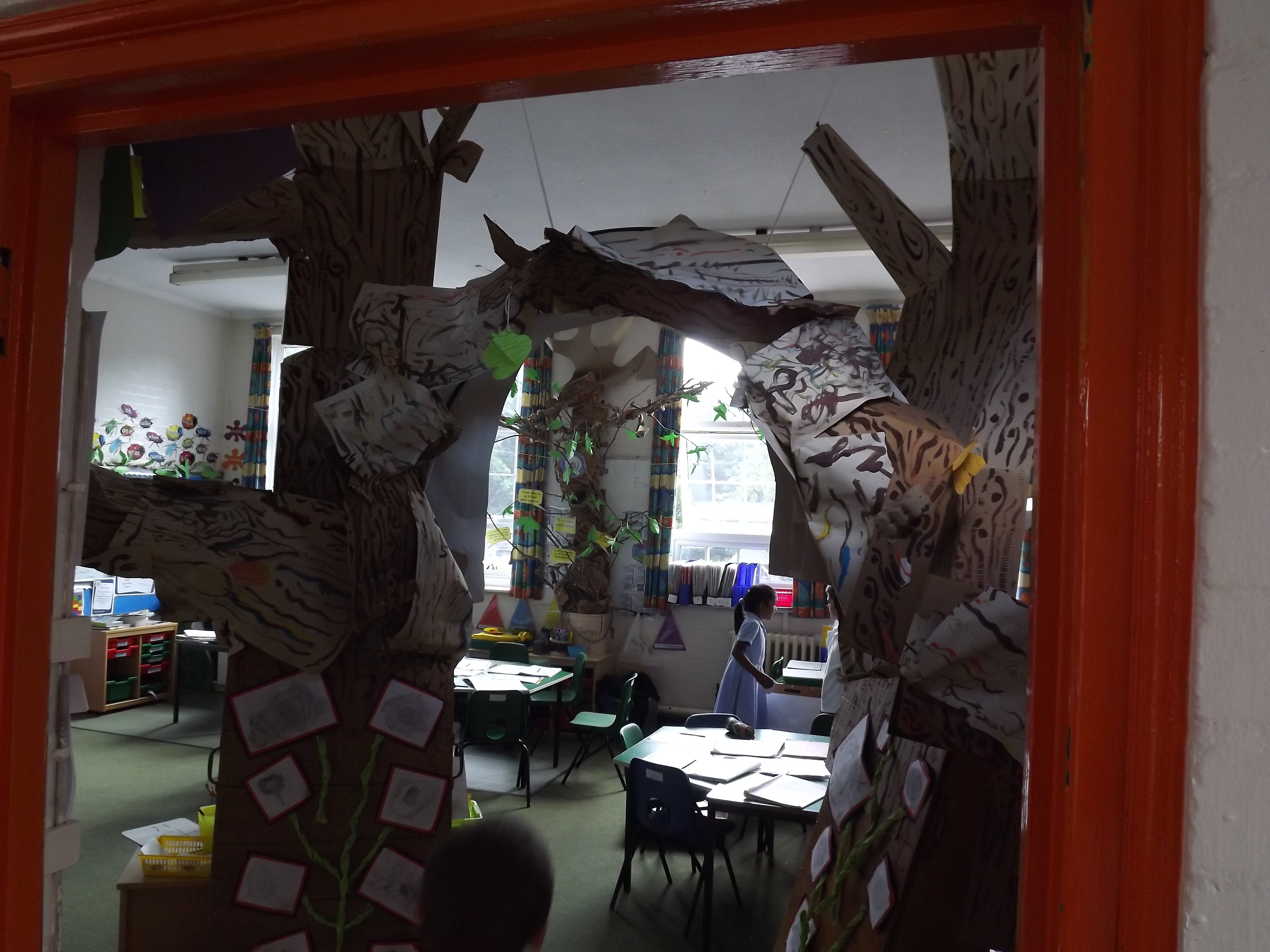

- First, is the room a simple, anonymous “box” or does it include distinctive design features? These may be already built in to an extent, say, through a complex floor plan shape or unusual ceiling design or it may be that the teacher has to work harder, with their class, to make the space their own. This could involve fairly large-scale class-made displays that are instantly recognizable (whilst of course avoiding creating too much visual stimulation). For example, I will not forget the classroom that had in it a full size tree made of painted cardboard boxes that you had to walk under as you entered! It can be worth making an effort to signal the entrance of the classroom in the corridor outside, so that pupils have no doubt when they have arrived at their “home” base.

- Second, do the pupils get the opportunity to put their personal mark on the classroom? Can they see themselves in the space? A big element of this is for pupils’ work to be displayed on the walls and in other examples of their efforts. Sometimes there are extensive displays but it is all teacher-created learning materials. Do the pupils have individual trays, pegs, lockers? If so, do the have their names on them, and maybe small photographs of their faces? The overriding thing to assess is: does this classroom obviously belong to these pupils?

- Third, is the classroom really thought through for children of the given age. This concerns the provision of good quality desk and chairs of the appropriate size, together with furniture and fittings that create a child-centred space that makes the pupils feel comfortable and valued. In this connection it is striking that through work in Norway we have seen excellent provision in some respects, such as fully adjustable chairs, but at the same time high quality, but very severe desks and cupboards that create quite an alienating feel for young children. Other aspects that can be addressed are low level sinks and interactive whiteboards that children can reach and low sill levels to windows so views out are available and maybe window seats are provided.

Flexibility

This aspect is built up of physical features of the classroom that deliver options to pupils and to teachers about how they access learning opportunities. Aspects include: the availability of different spaces, plenty of wall area for display and plenty of storage. Some of these will be relatively fixed through the initial design of the classroom, but others will be dependent on how the space is set up and used.

- First and foremost are there well-defined learning zones within the classroom? This involves areas such as: reading, role-play, maths, wet area, carpet area. Ideally these need to actually feel like distinct areas, so if they can be accommodated within natural recesses in the shape of the classroom this is good. If not, then they can be formed through the use of furniture, but it is good if they can also be defined by changes in colour and / or level otherwise a rather chaotic feel can be created raising visual complexity / stimulation issues! Learning zones link to the pedagogy employed of course and so more are generally appropriate with younger pupils at KS1, whereas fewer are normally needed in KS2 (but not none) and space can often be at a premium as the children, and so desks and chairs, tend to be bigger, but often the classroom is not! One issue we have noticed through many observations and conversations with pupils is that they love “found” or part-made spaces where they have permission to form the spaces as they choose – it is possible to try to hard to provide all they need.

- Second, is there a breakout space associated with the classroom for one-to-one or small group work? This may be shared, but provides an invaluable extra dimension for the teacher to set up different activities and deliver them without clashing with the main classroom. This flexibility can be distinguished from having lots of open space, which does not support different, but adjacent activities in the same way.

- Third, there is a need for sufficient wall area to flexibly support the creation of wall displays as discussed under “ownership”. Such spaces can easily be lost where there are large windows andhigh storage cupboards. That said, the common solution of putting display material up on the windows is not the answer as it hits day-lighting negatively, which is an important “naturalness” factor.

- Fourth, there is always a need for sufficient storage that is accessible to the teacher and pupils. Sometimes this may be difficult to achieve in the classroom itself and, if the corridors are sufficiently wide, it can be augmented with the provision of cupboards and maybe lockers in the space outside the classroom. Without adequate provision the opportunities for the class to switch activities, using different learning materials will be hampered.

Conclusion

The issue of individualisation in the classroom deserves higher prominence, particularly as its impact on learning has now been evidenced. In fact when progress in mathematics specifically was investigated, individualisation was found to be the biggest factor. It would seem that pupils feeling comfortable in their classroom pays real dividends for this subject where often confidence issues are experienced.

As can be seen from the discussion above, there are many choices that teachers can make to improve the experience of their pupils in terms of individualisation. Often teachers would have done some of these things intuitively, but now a more comprehensive approach can be taken. Some aspects can be facilitated by the basic architectural design of the classroom and of course wherever possible designers should be sensitive to these and create classrooms that naturally support teachers and pupils in making them their own.